Paul Smith, Impressionism and the Impressionists

Theories of Impressionism

Impression , Sunrise, like many other paintings in the first exhibition, was hotly discussed by the critics and, probably, by the public. It is perhaps difficult to appreciate this now, since Impressionist painting has become familiar through a vast number of reproductions. But it is not just the familiarity of reproduction which has tamed Impressionism; it is also the kind of interpretation it has received. Broadly speaking, this has taken two forms until comparatively recently. According to the first - the Formalist and Modernist view - Impressionism's interest lies largely in its "flatness," or the way it draws attention to its own "surface," or its nature as "paint" laid upon a support, as if this were somehow expressive in itself and in some way that, say, the paint on a wall is not. According to the other kind of interpretation - the biographical - Impressionism is interesting because of the Impressionists' determination to pursue a new style in the face of opposition from the reactionary institutions of art and the conservative press and public. On this view, Monet's painting is interesting because it attests to the courage of the artist, his "genius," and the triumph of progress over stagnation.

These approaches have many shortcomings. Modernism has very little to say about just what it is that makes paint expressive. Biographically based accounts of Impressionism tend to emphasise the personality behind the picture at the expense of the picture itself. Moreover, both approaches also tend to obscure the relationship between a painting and its wider history simply by writing this issue out of consideration. In particular, the idea that art owes its virtue to the heroic individual who made it eliminates from Impressionism any account of its determination in the wider world , and any account of its political meanings.

Edouard Manet, Fifer (1866)

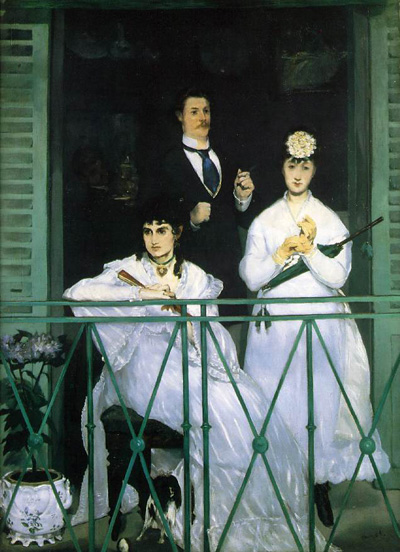

Edouard Manet, The Balcony (1868-69)

Because of these shortcomings, art historians have looked for other approaches with considerable vigour in recent years. These new perspectives on Impressionism - or revisionist histories - are roughly of four overlapping kinds: social-historical, feminist, psychoanalytical, and what I shall tentatively call anthropological.

Social-historical interpretations mostly fall into two varieties, anecdotal and theoretical, sometimes crudely labelled "Marxist". By and large, the anecdotal, social history of art is interested in analysing the contents of works of art in terms of what went on in the everyday social life they represent. Sometimes it tries to find significance in a painting as though its contents symbolised some value or belief. Thus, Impression, Sunrise might be seen as an interesting painting because of what it tells us about the social life in the docks at Le Havre, or because its imagery of the day breaking over the thriving port could be seen as a symbol of the regeneration of France after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

In the main, theoretical social histories of Impressionism try to estimate the extent to which Impressionist paintings issued from, served, or resisted dominant ideology - the middle-class, white, and masculine beliefs that posed or were accepted as truth at the time (see Chapters Two and Three). Using this sort of thinking, we might want to ask of Impression , Sunrise whether or not it challenged conservative and authoritarian conceptions of artistic merit, such as the Academic doctrine which held that a painting's value lay in its ability to aspire to timeless (classical) beauty and the unique moral order that this supposedly exemplified. In Academic theory, beauty was nearly always connected with morality, some theorists claiming that this was because beauty was Divine in origin, which might seem a very strange claim when confronted with an Academic painting such asWilliam Adolphe Bouguereau's Nymphs a11d Satyr (1873) or Cabanel's Venus. Equally, we might want to ask whether or not Monet's painting expressed other beliefs about artistic quality which might be tied to the ideologies being consolidated by the emergent bourgeoisie from which he came. For instance, we could ask whether or not it expressed sympathy with the idea that the individual could choose his or her own subject matter and standards of beauty and, if so, whether this links the painting with ideologies of individualism held to be central to the identity of the bourgeoisie. . . .